Rules of Inheritance (ON)

There are a number of factors that impact ON estate inheritance, including wishes expressed in a will, province law, designated beneficiaries, legal family relationships, and even executor discretion.

Note that if the decedent was a resident of Quebec, the "estate" will officially be known as a "succession".

Before we begin, note also that there are several overlapping terms used to refer to people who inherit from an estate:

- Heir: Someone related to the decedent, who would normally inherit from the estate even without a will.

- Devisee or Legatee: Someone specifically named in the will. Historically, a devisee inherited real estate, and a legatee inherited personal property.

- Beneficiary: General term for someone who will inherit from an estate, but also specifically used for asset classes (such as RRSPs) that bypass probate and go directly to the person named.

To keep things simple, EstateExec uses the common term "heir" when referring to anyone who will inherit from the estate, and additionally uses the term "beneficiary" when dealing with assets that automatically bypass probate.

Inheritance by Will

If the decedent left a valid ON will, it may grant you a specific item from the estate (known as a bequest), and it may grant you a share of the overall estate.

Bequests

A bequest gives a specific asset or dollar amount to a particular heir (i.e., devisee or legatee).

For example, a will might state that:

- Sally Jones should receive the grand piano

- Tom Smith should receive $10K

Before you can receive the item named in a bequest, the estate must first satisfy any higher priority obligations, such as resolving debts, paying taxes, covering the costs of estate administration, and handling any family entitlements.

An estate must sometimes sell assets in order to be able to meet these obligations, but an executor has a duty to try to avoid selling any items named in a bequest.

Abatement: Regardless, particular bequests can sometimes be only partially honored: perhaps the estate is smaller than expected, or contains fewer items. In such cases, that bequest is said to undergo abatement, and required reductions are typically made proportionately to the recipients. For example, if the estate is worth $100K and there are several cash bequests that total $200K, all bequests would be reduced by 50%. Similarly, if the will bequeaths three pianos to a particular heir, and there are only two pianos in the estate, then the heir would receive just two pianos.

Ademption: Sometimes a particular bequest cannot be honored at all: perhaps the asset is no longer part of the estate; perhaps the bequest conflicts with local law (e.g., community property); or perhaps the asset must be sold (as a last resort) in order to pay estate debts. In such cases, that bequest is said to undergo ademption, and is effectively ignored. For example, if our example estate actually did not contain a grand piano at the time of death, then the bequest of the piano would simply be ignored. There are no "make-up" gestures an executor can do for the intended heir: the executor cannot buy a piano out of estate funds and then honor the bequest, and the executor cannot give the heir additional funds to compensate for the lack of a piano.

Residuary Estate Shares

If you are granted a share of an estate according to the terms of a will, you should receive the specified percentage of the residuary estate: whatever remains after all estate obligations have been met, and any bequests satisfied (to the extent possible).

For example, the will might specify that:

- Susan Smith should receive 25%

- Tina Godfrey should receive 25%

- Jose Martinez should receive 50%

If the gross estate were worth $300K, and had obligations of $100K (perhaps consisting of $50K in credit card debt, $30K in taxes, and $20K in estate administration expenses), the residuary estate would be worth $200K, and distributed according to the above percentages.

- Susan would get $50K

- Tina would get $50K

- Jose would get $100K

If the residuary estate, after resolving all obligations, consisted of a vehicle worth $20K and a bank account containing $180K, the executor could sell the vehicle and distribute the $200K exactly as above.

If it turned out that someone really wanted the vehicle, then it would be best practice for the executor to allocate the vehicle to that heir's share, but the executor is not required to honor such preferences. Similarly, if multiple people wanted the vehicle, the executor could use his or her discretion to decide to sell it, pick a particular recipient, or potentially allocate ownership to multiple recipients. For example, if Susan wanted the vehicle, the executor could distribute the estate as follows:

- Susan gets the vehicle and $30K (total $50K value)

- Tina gets $50K

- Jose gets $100K

Bequests are normally handled before the residuary estate is calculated, so if our example included a $20K bequest to Samuel Iacatelli, then the residuary estate would be worth $180K, not $200K, and the distributions would instead be:

- Samuel gets $20K (the bequest)

- Susan gets the vehicle and $25K (total $45K value)

- Tina gets $45K

- Jose gets $90K

However, people can get creative when writing their wills, and the will might actually specify that a certain heir should receive a particular asset as a part of his or her residuary share.

Intestate Succession

If the decedent left no valid will (i.e., died "intestate"), then inheritance is determined by province law according to legal family relationship (e.g., spouse, child, parent, first cousin, etc.). Different provinces define these intestate inheritance rights differently, but all give significant preference to a surviving spouse and direct children. If no spouse or children survive, then typically the children of the children would inherit. If no direct descendants exist at all, then inheritance typically reverts to the deceased's parents, siblings, grandparents and other next of kin.

If you have been notified that you are entitled to an inheritance due to intestate succession, your inheritance will be equal to the percentage share, as specified by law, of the residuary estate, meaning the estate after all other obligations have been met, such as debts, taxes, and any family entitlements.

For example, if you are entitled to a 10% share of an intestate estate worth $200K after all obligations have been met, you should receive $20K.

Not everything in an estate is cash, however, so your share might include physical items such as a vehicle or a house. Your share might even include partial ownership of something, such as a business, shared with other heirs. An executor may sell assets for various reasons (to pay off debts, or even just to simplify distributions), but is not required to do so. You may express a preference to the executor that your share include certain estate assets, but the executor is not required to honor those wishes.

For example, if an estate included a $20K vehicle, a $5K grand piano, cash equivalents of $200K, and a $500K house, the estate would be worth a total $725K. If estate debts, taxes, and other expenses totaled $125K, the residuary estate would be worth $600K. If you were entitled to 10% of the estate, you would therefore inherit $60K, which could take the from of $60K in cash, or perhaps the vehicle plus $40K in cash. Best practice is for an executor to respect your wishes in terms of the exact contents of your share, but ultimately the executor can allocate share contents as he or she sees fit.

If An Heir Has Died

If an heir died after the decedent, then that heir's estate simply inherits whatever that heir would have inherited.

If an heir died before the decedent, then the following rules generally apply in priority order:

- If the will names an alternate recipient, then the alternate receives the inheritance instead.

- If the recipient was not specifically named, but was instead simply part of a group (i.e., "my children"), then the remaining members of the group split the inheritance among themselves.

- Some wills specifically state that any bequest to a pre-deceased person should instead become part of the residuary estate, and thus be distributed to the residuary heirs along with everything else.

- Otherwise, the particular province's "anti-lapse" laws may apply if the intended heir was a lineal descendant of the decedent (or even just a sibling in some provinces), generally assigning the inheritance to the dead heir's relatives, in a particular priority order (as long as the will does not specifically exclude this). If you are uncertain as to who should inherit in this case, you may want to speak to an estate lawyer.

- If none of the above conditions are met, then the property becomes part of the residuary estate, and is distributed to the residuary heirs along with everything else.

- If there are no surviving residuary heirs, and the province's anti-lapse statute did not apply (perhaps because there were no qualified blood relatives of the deceased residuary heirs), then the residuary estate is distributed according to the province's laws of intestate succession (as if there were no will).

ON Family Entitlements

Regardless of whether there is a will or not, many provinces have laws designed to protect a surviving spouse and dependents, ensuring that they receive at least a minimal amount from the estate as they try to put their lives together and move on. These entitlements usually have precedence over debt claims (other than funeral and estate administration expenses), and even distribution wishes expressed in a will, or intestate succession calculations.

Typical entitlements include personal property exemptions, a homestead, and a family living allowance. Many provinces also provide for a surviving spouse elective share, which allows a spouse to disregard the will and instead claim a share of the estate as mandated by law. In contrast to other family entitlements, a spousal elective share is normally calculated after all debts (and any other obligations) have been resolved.

Ontario allows a surviving spouse to claim certain entitlements:

Matrimonial Home

A surviving spouse is entitled to remain in the matrimonial home, rent free, for at least 60 days following the death (see Family Law Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. F.3, s 26(2)).

Family Support

If the portion of the estate that would normally go to a dependant is inadequate for his or her proper maintenance and support, the court may reallocate intended estate distributions to resolve the situation. In order for the court to intervene, an application for such support must be made within 6 months after the grant of probate or administration, or before the estate is completely distributed in any case. See Succession Law Reform Act, RSO 1990, c S.26, s 57.

Surviving Spouse Elective Share

Regardless of what the will says, a surviving spouse who was legally married to the decedent is optionally entitled to claim 1/2 of the net family estate. Specifically, if the net family property of the deceased spouse exceeds the net family property of the surviving spouse, the surviving spouse is entitled to one-half the difference between them (see Family Law Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. F.3, s 5(2)).

Note that the following property is generally excluded from the definition of net family property:

- Property, other than a matrimonial home, that was acquired by gift or inheritance from a third person after the date of the marriage

- Income from such property, if the donor or testator expressly stated it is to be excluded from the spouse’s net family property

- Damages for personal injuries

- Proceeds of a life insurance policy

- Property, other than a matrimonial home, into which the above funds can be traced

- Property that the spouses have agreed by a domestic contract is not to be included in the spouse’s net family property

- Unadjusted pensionable earnings under the Canada Pension Plan

The elective share is primarily a distribution allocation exercise; the elective share has no special protection from creditor claims.

To make such an equalization claim, the surviving spouse must file an election in the office of the Estate Registrar for Ontario within 6 months of the death.

Automatic Transfers

Several types of inheritance happen "automatically" (unless the estate is in Quebec). To collect these "automatic" transfers, you will likely have to fill out a few forms, but probate will not be required, and the transfers will not be under the control of the estate executor.

For example, if you owned property together with the decedent, with joint right of survivorship, you and any other co-owners will automatically become the remaining owners of the property upon the death of the decedent. If the property is real estate, you will usually want to contact the local registrar to get the deed and tax records updated, but the transfer should be automatic.

Additionally, if you are the named beneficiary of certain types of assets (e.g., RRSPs, life insurance), you will automatically be granted ownership of the assets upon the original owners death. Such transfers usually only require that you show proof of death to the asset holder (i.e., the financial institution), but the process by which such funds are transferred, and the account into which they are placed, may have important tax implications, so you are advised to seek the help of a tax professional.

Additional Information

For more information about inheritances in general, see EstateExec Heir Guide.

In case you're interested, inheritance rules in other provinces can be found here:

Estate Obligations & Insolvency

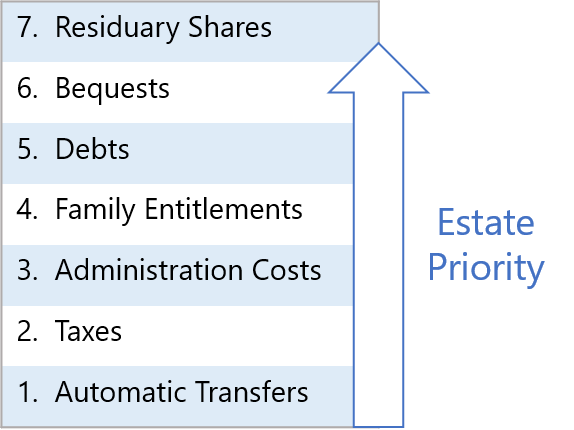

As mentioned in the preceding sections, an estate must allocate its resources in a defined priority order. Certain transfers (such as to RRSP beneficiaries) happen automatically outside the control of the estate, and the estate itself must then ensure it has enough funds to pay all taxes, then estate administration costs, then any family entitlements, then any general debts, and with anything left over, fulfill any will bequests, and finally distribute the residuary estate.

Province law determines which debts have priority over other debts, and some debts (such as funeral expenses) often have priority over family entitlements, but these specifics are the responsibility of the estate executor, and really only matter if the estate cannot pay all its bills.

If the estate runs out of money paying one tier, then subsequent tiers are left with nothing. Consequently, even if you have been bequeathed an item, or are entitled to a residuary share of an estate, you may end up with less than expected. If the estate cannot pay all its debts, the estate will be considered insolvent. If the estate turns out to be insolvent, you will not receive anything at all ... but neither will you be responsible for the remaining debts. However, some provinces do allow creditors to pursue recipients of automated transfers if the estate cannot pay their claims, so if you received an automated transfer, it is possible you would have to pay some or all of it to an estate creditor (this is rare).

EstateExec™ Leaves More $ for Heirs!

EstateExec will likely save the estate thousands of dollars (in reduced legal and accounting expenses, plus relevant money-saving coupons), leaving more funds for distributions to heirs.

- Awarded Best Estate Executor Software in North America at the Worldwide Finance Awards

- Named Best Estate Executor Tool – – by Retirement Living

- Web Application of the Year Winner at the Globee Business Excellence Awards 2022

- Winner of Best Executor Software at the Software and Technology Awards

- Rated 4.9 stars – – on TrustPilot reviews